FOR RELEASE on June 12, 2023

Contacts:

Michael Hallworth, PhD, Data Scientist

Emily Anderson, Communications Director

Kent McFarland , VAL Director

New Report Uses Big Data to Establish Vermont Biodiversity Baseline

NORWICH, VT–By 2100, Vermont is estimated to experience a net loss of 386 species (or 6%), under the current carbon emission scenario. This comes among several key findings outlined in a new report from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE). Their report marks the 10th Anniversary of the Vermont Atlas of Life, an ambitious project that harnesses the power of community science and professional biologists to discover, document, and map Vermont’s biodiversity.

The report uses nearly 8 million observations from almost 12,000 species reported from across the state to help establish a biodiversity baseline for Vermont. As the researchers explain, this baseline is critical for understanding and measuring future biodiversity changes caused by landscape alteration, climate change and other environmental perturbations.

“Using these vast amounts of species observations, we’re able to identify biodiversity hotspots and areas that harbor unique communities found nowhere else in Vermont. We’re also able to predict where they might be in 50 or even 100 years as the climate changes,” says Dr. Michael Hallworth, a data scientist at VCE and lead author of the report.

In addition to predicting future species loss, the report also found that current land conservation configurations may not be adequately protecting some of Vermont’s most at-risk species. By identifying areas that currently support unique communities—like the Lake Champlain Basin—Dr. Hallworth and his co-authors indicate areas that may be critical for maintaining biodiversity in the state.

The Vermont Atlas of Life (VAL) couples the power of volunteer community science with traditional biodiversity research and monitoring to quantify species diversity now and into the future. VAL joins others across the globe in curating species occurrence records at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), an international network funded by the world’s governments and aimed at providing anyone, anywhere, open access to biodiversity data. With these data, scientists and conservation professionals are discovering, monitoring, and solving biodiversity issues ranging from local to global significance, similar to the research team at VCE.

“We have centuries of open access weather data that has allowed us to monitor and understand climate change; we need the same for biodiversity,” says Kent McFarland, Director of VAL and co-author of the report.

Although these species occurrence records are derived from many sources—from historical museum specimens to field observations—over 95% are submitted by community scientists through VAL-supported platforms like Vermont eBird, iNaturalist, and e-Butterfly.

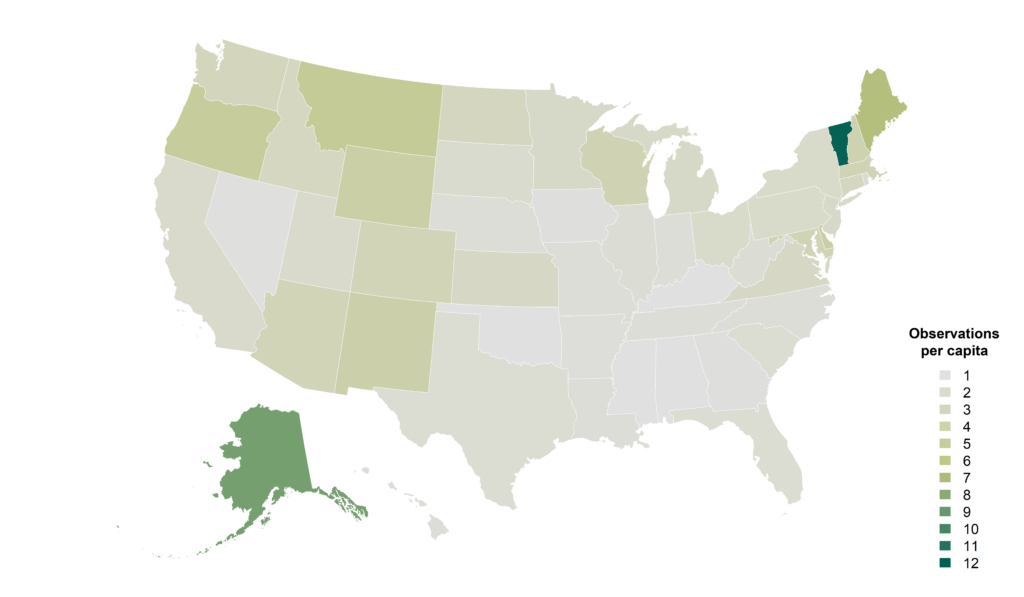

“Vermonters have risen to the conservation challenge: our volunteer community scientists lead the nation with more field observations per capita than any other state,” says McFarland. “All of these data are curated at GBIF and searchable using the VAL Data Explorer on our website at val.vtecostudies.org/gbif-explorer. Without volunteer community scientists’ dedication to documenting Vermont’s nature, this report—and our work more broadly—wouldn’t be possible.”

These data provide the basis for many quantitative studies that can inform effective regional and global conservation decisions. In this report, the scientists draw upon this treasure trove of biodiversity data to better understand how many species there are and where they occur in the state. They also couple the occurrence records with climate and other environmental data to generate species distribution models, which allow inferences about what species may occur in areas of the state that are not well sampled. These models are essential for assessing conservation status and extinction risk, tracking population change, and guiding conservation efforts.

“The findings presented in this report allow us to see Vermont’s landscape in new ways. We’ve identified potential biodiversity hotspots and made predictions about future impacts of climate change on the state’s biodiversity,” concluded Hallworth. “Together, this information will help target land conservation efforts, and much more.”

Report Key Findings

- The Vermont Atlas of Life has data for nearly 12,000 species across Vermont from 7.7 million occurrence records derived from museum specimens, photographs, and observations by biologists, naturalists, and community scientists.

- Vermont conservation lands, as currently configured, may not be adequately protecting at-risk species. The coverage area for at-risk species (Critically Imperiled: 12%, Imperiled: 17%, Vulnerable: 13%) was similar to species ranked as Secure (12%) or Apparently Secure (14%).

- Only a quarter of Vermont is conserved. By 2100, our current conservation lands will protect approximately 11% of species’ ranges, down from 13% today. Private lands are and will continue to be key for conserving and supporting biodiversity into the future.

- By 2100, the number of species found in Vermont is expected to decline by at least 6%, a net loss of 386 species, under the current carbon emission scenario (RCP 8.5).

- Areas that support unique communities are critical for maintaining biodiversity in the state. The southern Lake Champlain Basin harbors the most unique communities of any region in Vermont. By 2100, higher elevations in the state are predicted to shelter more unique communities.

- Our distribution models show that most species ranges are largely influenced by physical attributes of the landscape, such as underlying bedrock and soil characteristics. For many taxa, bioclimatic variables associated with precipitation are more important than temperature for determining their distributions within Vermont.

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 96 species found in Vermont that are of global conservation concern. Seven animal and three plant species are Federally Endangered.

- Only 28% of Vermont’s species have a state conservation rank. There are entire taxonomic groups that have no conservation status assessment because of insufficient data. Over 200 species (164 plants and 53 animals) are listed by Vermont’s Endangered Species Law.

- Climate and land-use change present significant conservation challenges that require an understanding of species populations at large scales. Partnerships between scientists and the public, through the Vermont Atlas of Life, are providing key information now and peering far into the future.

-30-

Watch a recording of a webinar presented by the lead author at https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/836249930

Images Available for Use:

Community scientists in Vermont lead the nation with more biodiversity observations shared per capita with the Vermont Atlas of Life and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility than any other state.