Key Findings

Key Findings

- The Vermont Atlas of Life has data for nearly 12,000 species across Vermont from 7.7 million occurrence records derived from museum specimens, photographs, and observations by biologists, naturalists, and community scientists.

- Our distribution models show that most species ranges are largely influenced by physical attributes of the landscape, such as underlying bedrock and soil characteristics. For many taxa, bioclimatic variables associated with precipitation are more important than temperature for determining their distributions within Vermont.

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 96 species found in Vermont that are of global conservation concern. Seven animal and three plant species are Federally Endangered.

- Only 28% of Vermont’s species have a state conservation rank. There are entire taxonomic groups that have no conservation status assessment because of insufficient data. Over 200 species (164 plants and 53 animals) are listed by Vermont’s Endangered Species Law.

- Vermont conservation lands, as currently configured, may not be adequately protecting at-risk species. The coverage area for at-risk species (Critically Imperiled: 12%, Imperiled: 17%, Vulnerable: 13%) was similar to species ranked as Secure (12%) or Apparently Secure (14%).

- Only a quarter of Vermont is conserved. By 2100, our current conservation lands will protect approximately 11% of species’ ranges, down from 13% today. Private lands are and will continue to be key for conserving and supporting biodiversity into the future.

- By 2100, the number of species found in Vermont is expected to decline by at least 6%, a net loss of 386 species, under the current carbon emission scenario (RCP 8.5).

- Areas that support unique communities are critical for maintaining biodiversity in the state. The southern Lake Champlain Basin harbors the most unique communities of any region in Vermont. By 2100, higher elevations in the state are predicted to shelter more unique communities.

- Climate and land-use change present significant conservation challenges that require an understanding of species populations at large scales. Partnerships between scientists and the public, through the Vermont Atlas of Life, are providing key information now and peering far into the future.

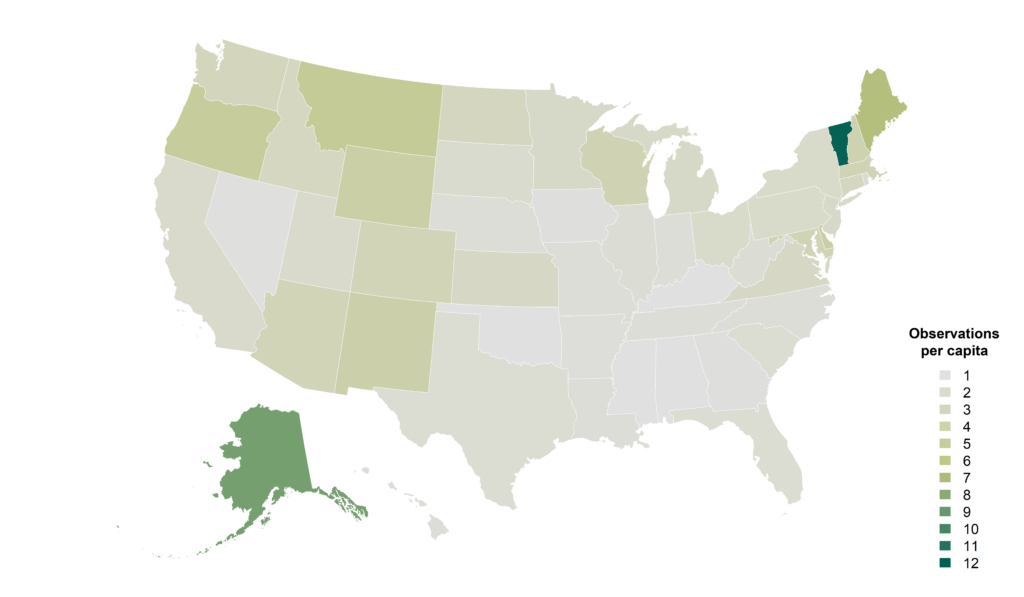

Community scientists in Vermont lead the nation with more biodiversity observations shared per capita with VAL and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility than any other state.

Executive Summary

A decade ago, the Vermont Center for Ecostudies launched the Vermont Atlas of Life (VAL) to aggregate data on species in Vermont and begin filling gaps in our collective knowledge. Over the last 10 years, VAL has amassed nearly 8 million species observations and grown into a central library of primary biodiversity data, accumulating knowledge from the past and present.

At VAL’s core is the community of people contributing and using information about Vermont’s changing nature: occurrence records, population data, distribution maps, photographs, and other data—from backyard naturalists to scientists to policymakers. In short, VAL is one of the most ambitious and far-reaching biodiversity informatics projects ever undertaken in Vermont. The Vermont Atlas of Life is giving us a better understanding of what’s here, what’s not, and how biodiversity and species distributions change over time.

As human activity profoundly alters the map of life at local and global scales, humanity’s response requires knowledge of plant and animal distributions across vast landscapes and over long periods of time. Addressing threats to biodiversity requires foundational knowledge of what lives here and what we stand to lose if carbon emissions and environmental degradation patterns remain unchanged. Despite Vermont’s rural and verdant character, it isn’t isolated from

global change and, in many ways, offers a microcosm where we can monitor biodiversity and implement conservation actions that others might apply at their own scales elsewhere.

Over the past century, we’ve likely recorded nearly every bird species that has flown in Vermont (382 species) and every mammal (58 species) that has inhabited the state. However, many other groups remain an enigma. Vermont’s insect diversity alone may approach 22,000 species, but no one really knows. Furthermore, for most species and many groups

Community scientists in Vermont lead the nation with more biodiversity observations shared per capita with VAL and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility than any other state.

Executive Summary

of organisms, no reliable assessments of their distribution or population trends exist. The Vermont Atlas of Life is helping to close that knowledge gap.

The Vermont Atlas of Life 10th Anniversary Report synthesizes VAL’s efforts over the last decade of gathering data to help establish a biodiversity baseline for Vermont. This report uses nearly 8 million primary biodiversity occurrence records, totaling almost 12,000 verified species recorded across Vermont—all curated at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and searchable using the VAL Data Explorer. Although these records are derived from many sources, from historical museum specimens to field observations, over 95% are submitted by community scientists through VAL-supported platforms like Vermont eBird, iNaturalist, and e-Butterfly. Vermonters have risen to the conservation challenge: our community scientists lead the nation with more field observations per capita than any other state.

High-quality biodiversity information is vital for science and conservation. One of the most critical components is primary biodiversity data. These data provide the basis for many quantitative studies that can inform effective regional and global conservation decisions. In this report, we draw upon Vermont’s primary biodiversity data to better understand how many species there are and where they occur in the state. In some cases, we simply summarize the primary biodiversity data to determine what has already been observed. However, for most analyses, we couple primary biodiversity data with climate and other environmental data to generate species distribution models, allowing us to make inferences about what species may occur in areas of the state that are not well sampled. These models are essential for assessing conservation status and extinction risk, tracking population change, and guiding conservation efforts. They allow us to see Vermont’s landscape in new ways, such as identifying potential biodiversity hotspots, understanding future impacts of climate change, targeting land conservation efforts, and so much more.