She moves through your garden with great stealth, hunting. She knows her next meal is here somewhere, and she can smell it. She creeps closer, closer. Suddenly, her prey is within striking distance; she just has to make sure it doesn’t sense her before she’s close enough to pounce. With a final rush of movement—success!

If you had looked out your back window towards your garden at this exact moment, you likely would not have seen this drama unfolding: a female lady beetle stalking an aphid through your peas. Most lady beetles (also called ladybugs) feed on small, soft-bodied insects, including aphids, mealybugs, and scale insects. And many of these insects can cause a lot of damage to garden plants and native flora if their populations grow too large.

Lady beetles are highly mobile and attracted to areas with high prey populations. They can smell both the chemical compounds released by host plants when under attack from lady beetle prey and/or the honeydew released by aphids and similar insects. Catching the scent of these compounds allows lady beetles to be more selective about where they feed and lay their eggs, seeking out prime, prey-ridden habitats for their offspring to mature.

For several reasons, our native lady beetle species are particularly well adapted for pest control. First, they are voracious predators throughout their lives. For example, a single larva of our native Hyperaspis binotata, measuring a mere 2.4 to 4.5 mm in length, is estimated to consume 90 mature scales and 3,000 plant pest larvae before pupating and emerging as an adult beetle. Second, many native species adjust their life cycles annually to align with population booms of their preferred prey species and actively hunt native prey much more efficiently than introduced lady beetles. Finally, some species, such as the Twenty-spotted Lady Beetle, feed on mildews and fungi that damage plants.

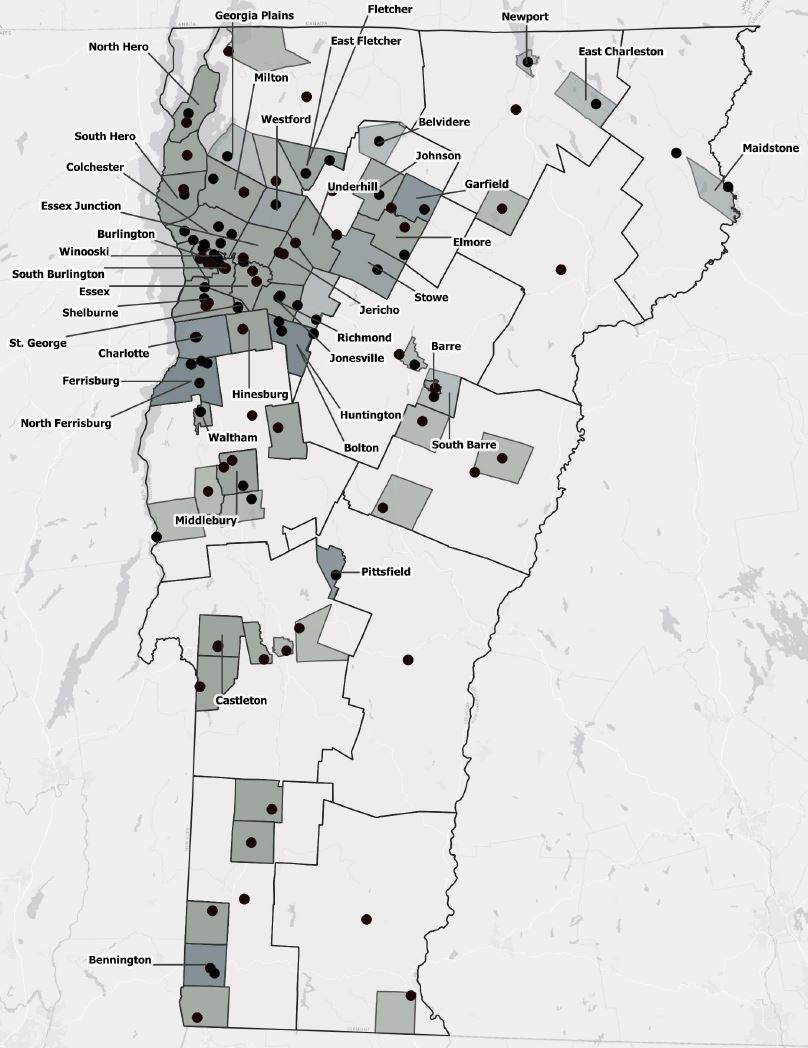

However, all is not well with our native lady beetles. Since 1968, some native lady beetle populations have declined by as much as 68% throughout their range. These declines are likely caused by introducing non-native species and diseases, land-use change, and pesticide use, with introduced lady beetles and land-use change thought to be the primary causes of decline. In Vermont, ten of our 36 native species have not been recorded in decades. The Vermont Atlas of Life (VAL) team started the Vermont Lady Beetle Atlas to understand our current lady beetle fauna better so we can inform conservation initiatives and policies surrounding these vital insects. Four of these missing species are of particular interest to the VAL team due to the sharp declines they have experienced across much of their range. All four once had ranges that spanned much of North America, and all have been documented as essential species in agricultural crops.

The Nine-spotted Lady Beetle (Coccinella novemnotata) is the first missing species of note. A habitat generalist, the Nine-spotted is usually found in agricultural fields, meadows, and prairies and seemed to begin declining sharply around 1980. This species can have up to two generations per year and is typically encountered between late June and August in the northern parts of its range. In Vermont, the Nine-spotted Lady Beetle was last seen in the Burlington and South Burlington area in 1996.

Our second focal species is the Two-spotted Lady Beetle (Adalia bipunctata), last documented in Burlington in 1996. In addition to crops, the Two-spotted Lady Beetle utilizes tree and shrub habitats.

The third focal species is the Transverse Lady Beetle (Coccinella transversoguttata), last seen in 1986 in Salisbury. This species was once one of the most abundant species found in crops. They are associated with early successional areas and edge habitats, particularly those containing lupine, willow sp., and clover. Transverse Lady Beetles likely have two to three generations per year in northern climates.

The Thirteen-spotted Lady Beetle (Hippodamia tredecimpunctata) is our final focal species. While preferred habitat includes reed beds and marshes, Thirteen-spotted Lady Beetles are frequent agricultural crop visitors. This species is most commonly found between July and August, taking approximately 20 to 28 days to develop from an egg to an adult.

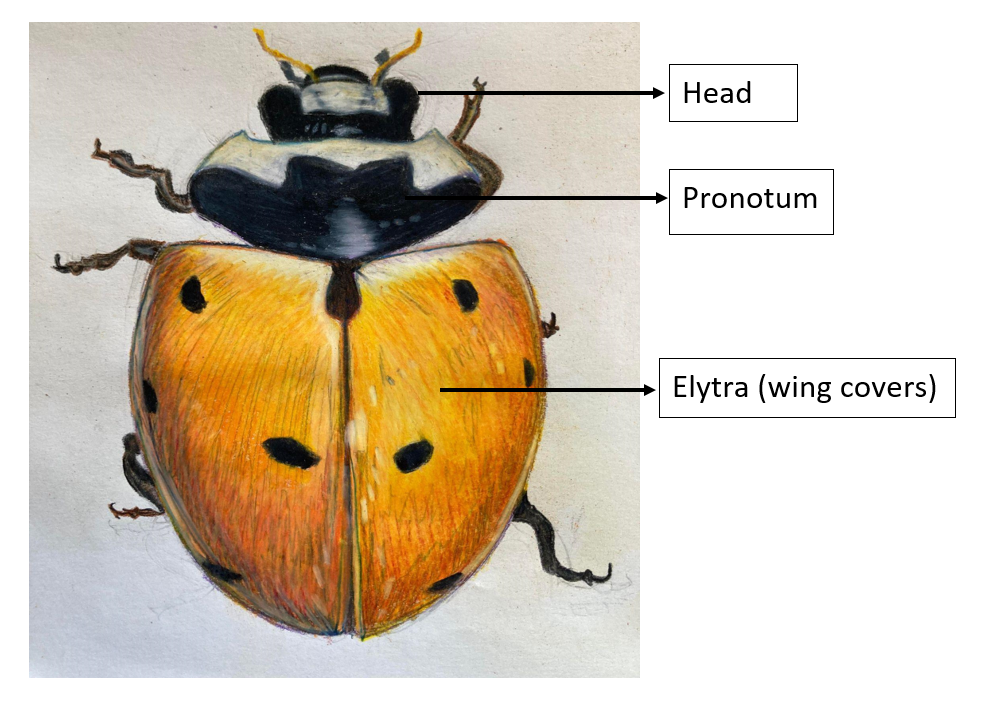

This summer, we are asking you to help us search for these four species (and document any other lady beetles you find along the way!). We have created maps that show every town where these species were recorded. This information and identification tips can be found using this link and view the information under “Focal Species Information – 2022 Field Season”. Take photos of each part of the lady beetle (head, pronotum, and elytra) and upload your pictures as an observation to iNaturalist. It helps if you bring a clear container into the field with you to place beetles in for photographing—they are fast and fly away quickly. For more information on searching for and documenting lady beetles, check out our Vermont Lady Beetle Atlas field manual.

Nine-spotted Lady Beetle © Julia Pupko

Towns where one or more of the four missing focal species were historically documented © Julia Pupko