The transition from the dog days of summer to the cool nights of autumn is upon us. We’re not the only ones that notice the changing temperatures. Trees are preparing for winter by reabsorbing nutrients from their leaves allowing their true colors to shine through. Many breeding birds along with a few migratory dragonfly species, moths and the iconic Monarch butterfly are preparing to migrate south for the northern winter. Resident animals are busy planning and preparing for the colder months that lie ahead. Small mammals are beginning to cache acorns, beech nuts and cones to dine on during the cold winter months.

Finding acorns, beech nuts and cones in the forest is easier in some years than others. Tree masting events or the synchronous fruit production across large areas, is a phenomenon caused at least in part by summer temperatures. In mast years, many individual trees produce an abundance of fruit in the fall. During mast years, there may be anywhere between a 3- to 9-fold increase in the amount of nuts and cones. As such, nuts and cones are plentiful, and many small mammals take full advantage of the bounty. With their coffers full of food, small mammals survive the winter at higher rates and have more young. Some small mammals increase their reproductive effort in anticipation of mast. The population response of small mammals to mast is noticeable and can even make news headlines.

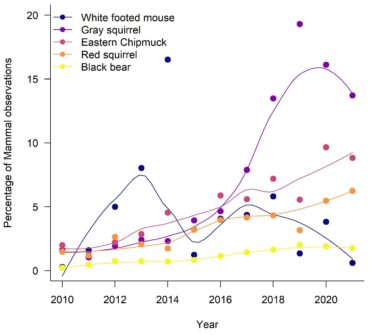

Small mammal observations shared with the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist increase in years following a mast, mirroring how their populations respond to tree mast. Mast in 2017 was considerable and followed several years without many acorns, beech nuts or cones. The last wide-spread mast event occurred in 2019. Will 2021 be a mast year? Will we see lots of small mammals as the snow melts next spring? Research from the White Mountains in New Hampshire indicates that the difference in summer temperatures between two consecutive summers predicts mast reasonably well. Therefore, the difference in the summer temperatures between 2020 and 2019 can give us an indication of whether this year will be a mast year (see maps). Based on the temperature data alone – it’s looking like 2021 may be a mast year but, only time will tell. Until then, be sure to submit your small mammal observations to iNaturalist and help us track tree masting events more accurately by adding your observations of trees with fruit by using annotations.

Small mammal observations shared with the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist increase in years following a mast, mirroring how their populations respond to tree mast. Mast in 2017 was considerable and followed several years without many acorns, beech nuts or cones. The last wide-spread mast event occurred in 2019. Will 2021 be a mast year? Will we see lots of small mammals as the snow melts next spring? Research from the White Mountains in New Hampshire indicates that the difference in summer temperatures between two consecutive summers predicts mast reasonably well. Therefore, the difference in the summer temperatures between 2020 and 2019 can give us an indication of whether this year will be a mast year (see maps). Based on the temperature data alone – it’s looking like 2021 may be a mast year but, only time will tell. Until then, be sure to submit your small mammal observations to iNaturalist and help us track tree masting events more accurately by adding your observations of trees with fruit by using annotations.

Occurrence Records

Annual Red Squirrel reports and Red Spruce and American Beech records from the Vermont Atlas of Life and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Most of these records are shared via iNaturalist from observers like you! Click on a year to see the Red Squirrel records with tree records in the background.

Predicting Masting

The map below shows the likelihood of mast production. Warm colors indicate a higher probability of mast while cooler colors indicate low probability of mast. All maps are based on the summer temperature differentials between the two preceding summers.