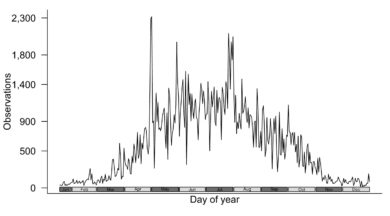

From Jim Armbruster’s observation of a Red Fox in the snow on New Year’s morning, to Levi Smith’s Tufted Titmouse eating seeds on New Year’s Eve, iNaturalists added over 202,000 biodiversity records to our rapidly growing database of life in Vermont in 2022.

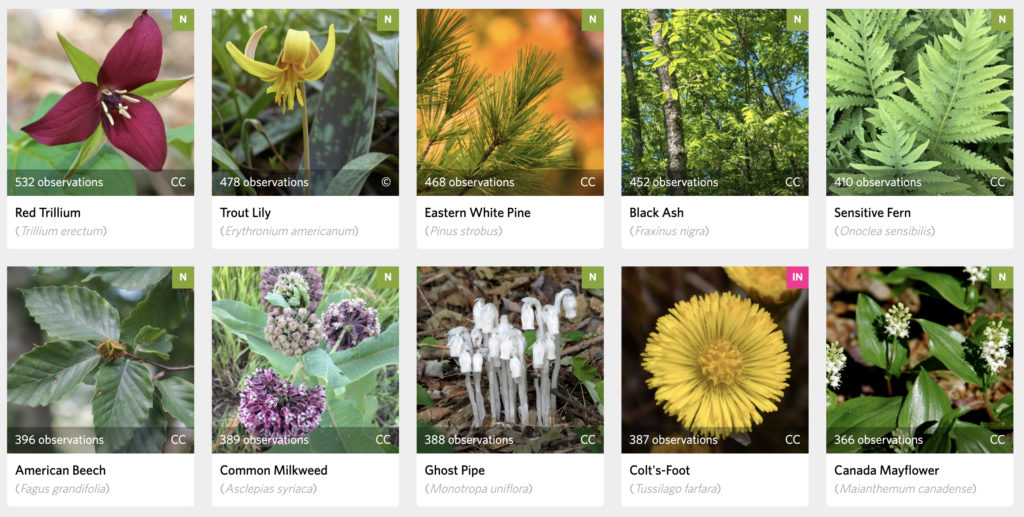

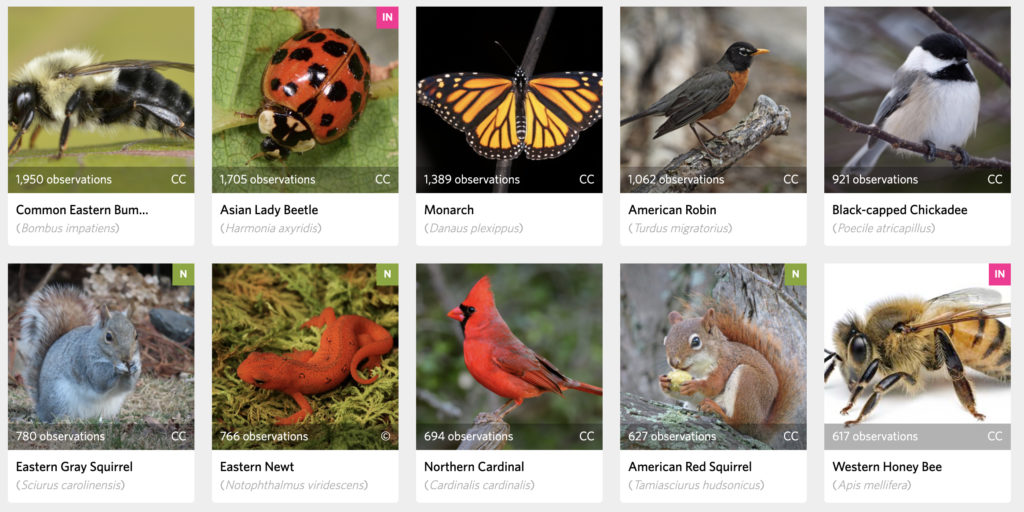

Top 10 species reported to iNaturalist Vermont in 2022. Click to on the image to explore at iNaturalist.

Amazing observations kept coming all year long. We had 4,756 species verified by 7,661 people, culminating in a total of 202,204 observationsin 2022. Over 4,220 naturalists and experts helped to identify and verify data.

We were not alone. Vermonters joined hundreds of thousands of iNaturalists worldwide that submitted over 33.7 million observations in 2022! Check out the 2022 year in review statistics dashboard, and if you’re an iNaturalist user, you can see your year in review too. Share it proudly on social media and tag it with #VTAtlasOfLife so we can see your discoveries too!

iNaturalist Vermont Surpasses Half Million ‘Research-Grade’ Records

This spring Tom Scavo snapped a photo of a Trout Lily and shared it to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist and Tom Norton soon agreed with the identification. It was something the both of them have done thousands of times, but this one was special. It was the 500,000th research-grade record for our project, making this the largest biodiversity database likely every collected for the state.

This is something we’ve all made together, but it’s larger than any one of us. Together, we’ve created a unique window into life in Vermont and thousands of species with whom we share the this amazing place. Thank you!

An observation submitted to iNaturalist becomes what is called ‘research grade’ when it has: a date, latitude and longitude coordinates, photos or sounds, and a 2/3 majority of agreement from iNaturalist community identifiers on the identification to species level. So far for 2022 (identifications keep on coming!), there are now 110,993 research grade observations representing 4,756 species.

It takes a village for an observation to become research grade. Other naturalists and scientists that can identify species help make these observations into research grade data. We had over 4,220 naturalists and experts help identify observations in 2022 alone. The top 10 iNaturalists in 2022 identified over 45% of all the verifiable records for the year. Thank you to everyone that helped identify observations!

| Rank | User | Identifications |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | tsn | 12,535 |

| 2 | peakaytea | 6,660 |

| 3 | trscavo | 5,075 |

| 4 | joannerusso | 4,623 |

| 5 | neylon | 4,344 |

| 6 | beeboy | 3,991 |

| 7 | johnascher | 3,618 |

| 8 | lynnharper | 3,221 |

| 9 | kevinhemeon | 3,206 |

| 10 | nsharp | 2,419 |

These research grade data are shared continually with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, an international open data infrastructure that allows anyone, anywhere, to access data about all types of life on Earth, shared across national boundaries via the Internet.

Highlights of New and Amazing Discoveries in 2022

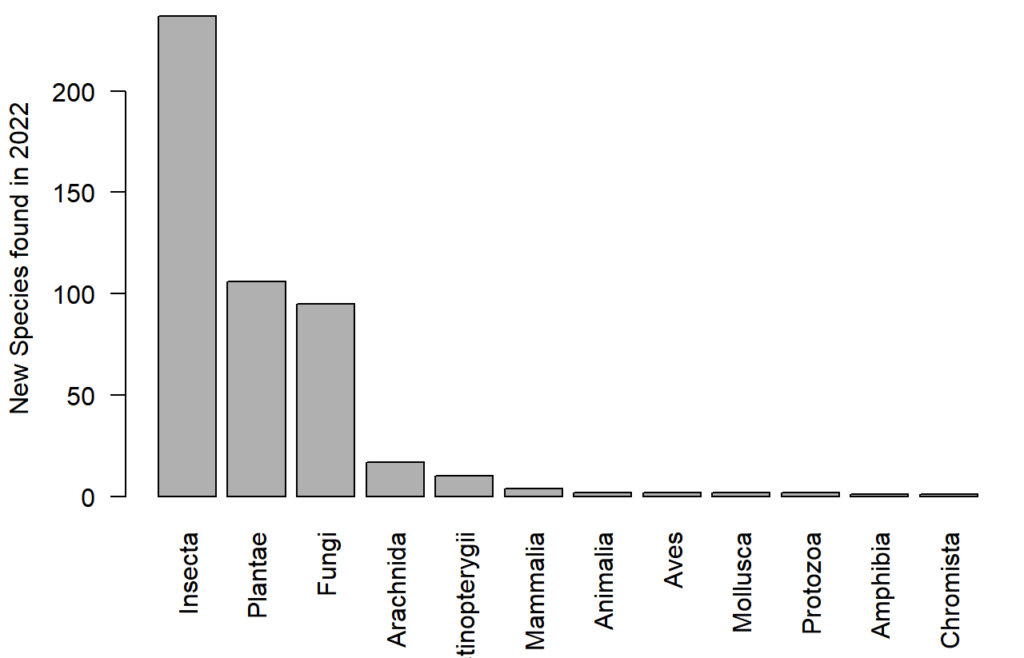

This year naturalists added hundreds of new species to the database for Vermont, many of these are perhaps completely new discoveries for Vermont.

Here are just a few highlights of species that caught our attention.

New Butterfly Species Recorded for Vermont on iNaturalist

In October iNaturalist James McNamara photographed a European Peacock Butterfly (Aglais io) in a garden in Calais, Vermont and reported it the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist marking the first state record for this species.

The species native range is in in Europe and Asia, but it was first found in 1997 in the Montréal, Québec region. A shipment of containers from Romania had arrived at the port a few days prior to the sighting and this may be the source of the introduction. It is now well established in the Greater Montréal area and extending into the southwest of the province.

In Québec, the European Peacock Butterfly overwinters and the adults fly from early spring to mid-September. They prefer open, sunny meadows, usually near woodlands, and borders of roads and railways, especially with Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) flowers, which is preferred for nectaring. Caterpillars feed on nettles (Urtica), which are abundant in the region.

It is likely that this record in Vermont originated from the introduced population in Quebec and we may discover more individuals and perhaps even breeding in the state. Next year be on the lookout for this introduced butterfly and report it to e-Butterfly.org or the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist.

The Vermont Butterfly Checklist is now comprised of 114 species in 5 families (Family:no. species= Hesperiidae 37, Lycaenidae 23, Nymphalidae 40, Papilionidae 6, Pieridae 8).

Federally Threatened Orchid Discovered in Vermont

A small whorled pogonia blooms on Winooski Valley Park District conservation land. VTF&W photo courtesy of John Gange

Botanists with the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department confirmed that a population of Small Whorled Pogonia—believed to be extinct in Vermont since 1902 and listed as Threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act—has been documented on Winooski Valley Park District conservation land in Chittenden County. The observation was first reported to the Vermont Atlas of Life project on iNaturalist last fall.

“Discovering a viable population of a federally threatened species unknown in our state for over a century is astounding,” said Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department Botanist Bob Popp. “It’s Vermont’s equivalent of rediscovering the ivory-billed woodpecker.”

The Small Whorled Pogonia is a globally rare orchid historically found across the eastern states and Ontario. Previous searches for the species in Vermont have been unsuccessful. As with many orchids, little is understood about the species’ habitat needs. Populations in Maine and New Hampshire are found in areas of partial sun including forest edges and openings. Read more on our Blog.

After 25 years, Two-spotted Lady Beetle is Rediscovered in Vermont

The Two-spotted lady Beetle.

The Two-spotted lady Beetle was feared to be extinct in Vermont, until the Vermont Atlas of Life rallied biologists and community scientists to help find them. Against all odds, several Two-spotted Lady Beetles were found and photographed after a 25 year hiatus.

Upon first glance, the small orange dot in the sweep net seemed unremarkable. But Julia Pupko, Eco-Americorps member and Vermont Lady Beetle Atlas coordinator, carefully scooped it into a glass vial to photograph. After a closer inspection of the beetle, its true identity astonished her. It was a Two-spotted Lady Beetle (Adalia bipunctata), a species of conservation concern, which hasn’t been seen in Vermont since 1996.

Many native lady beetle populations have declined throughout their ranges, and the Two-spotted Lady Beetle is no exception. These population reductions are thought to be caused by the introduction of non-native lady beetles, such as the Asian Lady Beetle. In a fairly short amount of time, the Two-spotted Lady Beetle went from being one of the most common native species, to a species of conservation concern in several U.S. states and Canadian provinces. Woodland habitats seem to be preferred, but the Two-spotted Lady Beetle was also an important predator in agricultural fields, helping to control aphids and other pests that harm crops.

“After realizing I had found a Two-spotted, I didn’t think the day could get any better,” said Pupko. “As I peered back into my net to see if I had successfully collected any other lady beetles, my jaw dropped–there was another Two-spotted in there!” Finding just one of these beetles is remarkable, but to find multiple individuals in one location further suggests that there is a breeding population at the Mills Riverside Park in Underhill.

More Lady Beetle Discoveries

Esteemed Sigil Lady Beetle

As Julia continued sweeping through the edge of the field, a second missing species was quickly discovered. “I was under 50 feet from where I found the Two-spotted beetles, checking my net. I noticed a small black speck running frantically across the fabric,” she said. “It just took one glance to know that I had found another missing species.” The Esteemed Sigil Lady Beetle (Hyperaspis proba) has never been commonly recorded in Vermont–there are only two prior records in the state. The last time it was documented was in 1972. Very little is known about this insect, but it is likely an arboreal species, which may be why it’s been recorded so infrequently.

Hyperaspis deludens © Julia Pupko

Pupko and VCE Biologist Nathaniel Sharp led a small group of volunteers down the Black/Maquam Creek Trail during the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge Bioblitz. Very few lady beetles had surfaced, and the group had shifted its focus from lady beetles to wild bees. “I half-heartedly swept my net across a blooming elderberry bush at a bee that had been effectively avoiding me for the past few minutes,” said Pupko. “Once I opened my net, I saw a tiny black lady beetle.” After photographing it extensively, the biologists determined that they were looking at something new to them. Pupko narrowed the species down to Hyperaspis deludens, which was confirmed.

Introduced Elm Zig-zag Sawfly Found in Vermont

First known record of Elm Zig-zag Sawfly in Vermont with distinctive feeding track on an American Elm leaf. Found and photographed by Owen Clark. Click to see the iNaturalist observation.

In 2020, It was first detected around Montreal, Quebec when an iNaturalist observer posted an image of its characteristic feeding pattern on an Elm leaf and experts noticed it. This fall, the Elm Zigzag Sawfly (Aproceros leucopoda) was found and reported to iNaturalist for the first time in Vermont in the northern Champlain Lake area. The larvae can defoliate an entire elm tree.

The adult is a small black, wasp-like sawfly with white legs. The larvae are tiny green caterpillars. Adult sawflies lay their eggs into the serrations at the edges of elm leaves and the larvae hatch within 4 to 8 days. The larvae develop over a further 15 to 18 days, feeding on the leaves. They then spin a cocoon on the underside of a leaf, emerging as adults within 7 days. With a short life cycle, the Elm Zig-zag Sawfly can produce several generations in one summer and infestations can happen very quickly. Additionally, no males have been found, which means the sawfly might reproduce by parthenogenesis (reproduction without fertilization), so its numbers can increase even more rapidly.

Plants Rule!

Plants clearly comprise the bulk of observations on the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist and 2022 was no exception. We had 5,181 iNaturalists contribute 70,626 observations comprising 2,042 verified species of plants. There were 480 introduced species reported and over 200 species of species with some level of conservation concern. Helping to verify records is another important part of the data. We had 1,450 iNaturalists help with this task. Tom Norton made over 11,000 plant IDs and he now has made over 464,000 identifications on iNaturalist. Thank you everyone!

Explore the 2022 Photo-Observation of the Month Winners

Each month, iNaturalists ‘fav’ any observation they like as a vote for the VAL iNaturalist photo-observation of the month. Check out the winners from 2022 (and other years too!) and learn a little bit about the natural history of each organism.

Help iNaturalist Vermont Surpass One Million Observations!

We are now approaching 1 million observations overall. Let’s keep it going. You can help by sifting through all the observations of others and help to verify any that you can so we can keep growing our research-grade data. Add more observations of your own, no matter how common or rare the species is, every observation is important. And you can help annotate observations with life stages, phenology of flowering, associated species, and many more annotations that help make the data even more rich for research and conservation.

Let’s make it a million, and learn about life in Vermont together! We hope you’ll join the project and help us make this biodiversity database grow. Make the Vermont Atlas of Life at iNaturalist your New Year’s resolution in 2023!