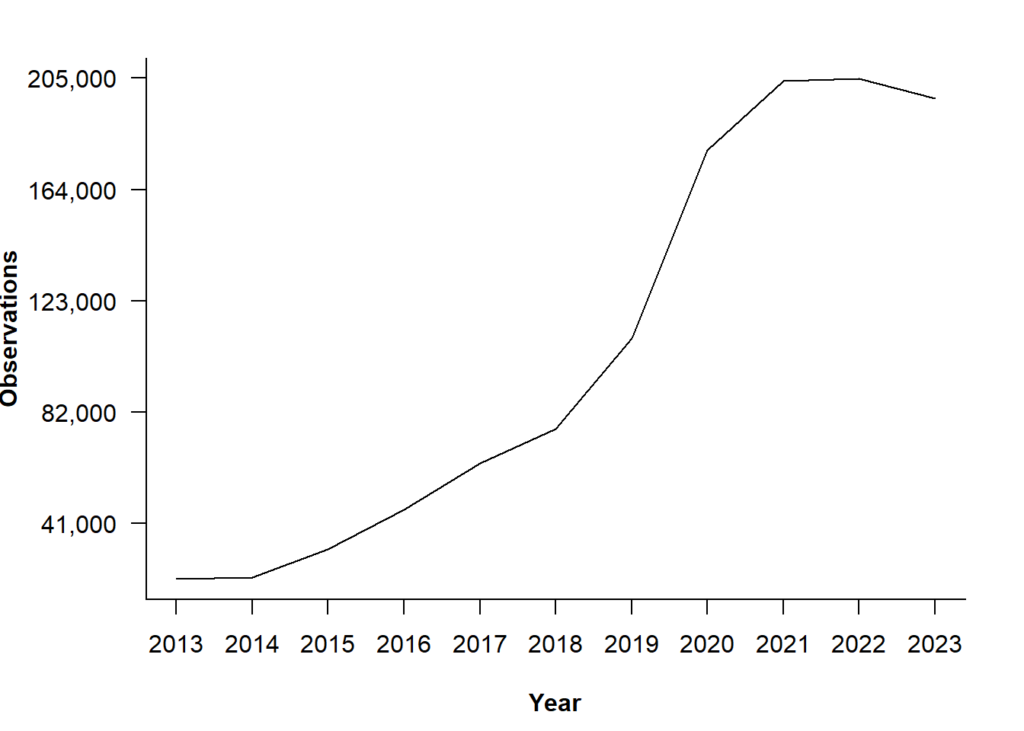

From Susan Elliott’s observation of Running Pine (Lycopodium clavatum) on New Year’s morning to Redbranch’s photo of American Amber Jelly Fungus (Exidia crenata) nearly a year later on New Year’s Eve, iNaturalists added over 200,000 biodiversity records to our rapidly growing database of life in Vermont in 2023.

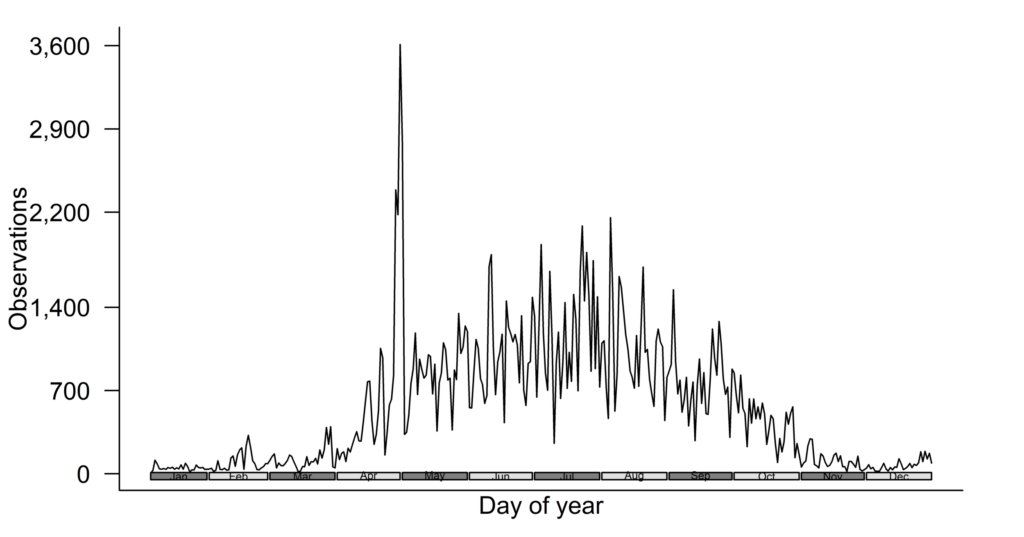

The number of daily observations submitted to the Vermont Atlas of Life project on iNaturalist in 2023 shows a massive spike during the City Nature Challenge in April, weekly oscillations mostly associated with weekends, and an uptick in December that could be associated with observers on Christmas Bird Counts.

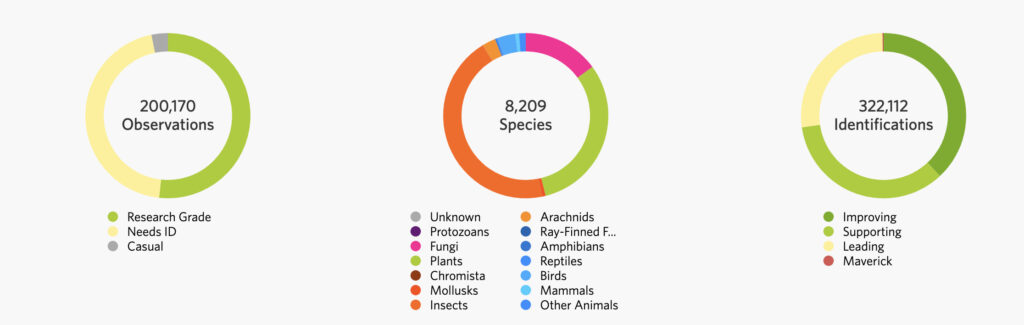

Amazing observations kept coming all year long, with the final tally rising to 200,170 observations reported by 7,771 iNaturalists. So far, we have over 103,494 research-grade observations comprising 4,939 species verified by 5,460 people from the 2023 data.

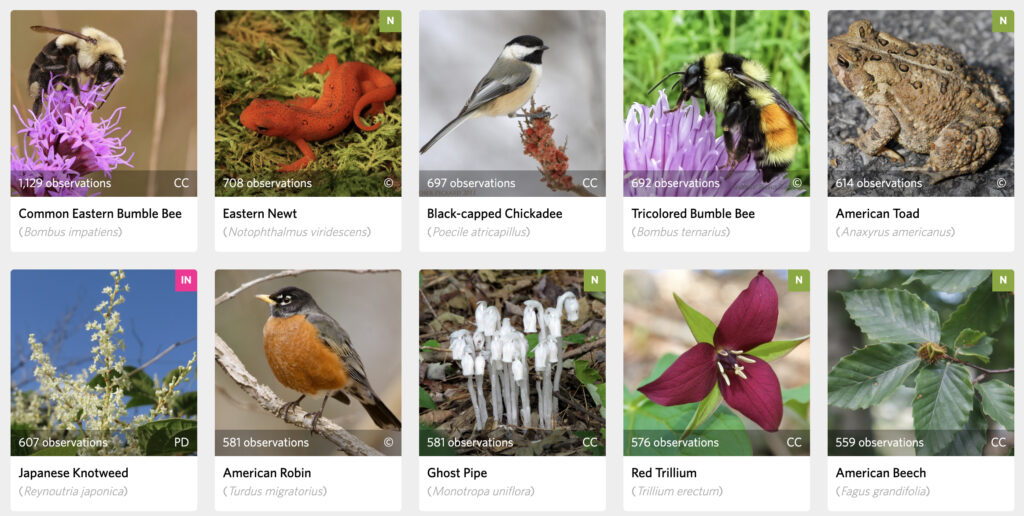

Top 10 species reported to iNaturalist Vermont in 2023. Click on the image to explore at iNaturalist.

We were not alone. Vermonters joined hundreds of thousands of iNaturalists worldwide that submitted over 41 million observations in 2023! Check out the 2023 year-in-review statistics dashboard, and if you’re an iNaturalist user, you can see your year-in-review too. Share it proudly on social media and tag it with #VTAtlasOfLife so we can see your discoveries, too!

Vermont Surpasses 1 Million Records on inaturalist

This spring, iNaturalist Caroline Greaser snapped a photo of newly sprouted bedstraw on April 30 during the 2023 City Nature Challenge, the millionth record for the Vermont Atlas of Life project on iNaturalist. In 2024, we are poised to break 1 million research-grade records! We’ve all helped to make this, but it’s larger than any of us. Together, we’ve created a unique window into life in Vermont and the thousands of species with whom we share this amazing place. Thank you!

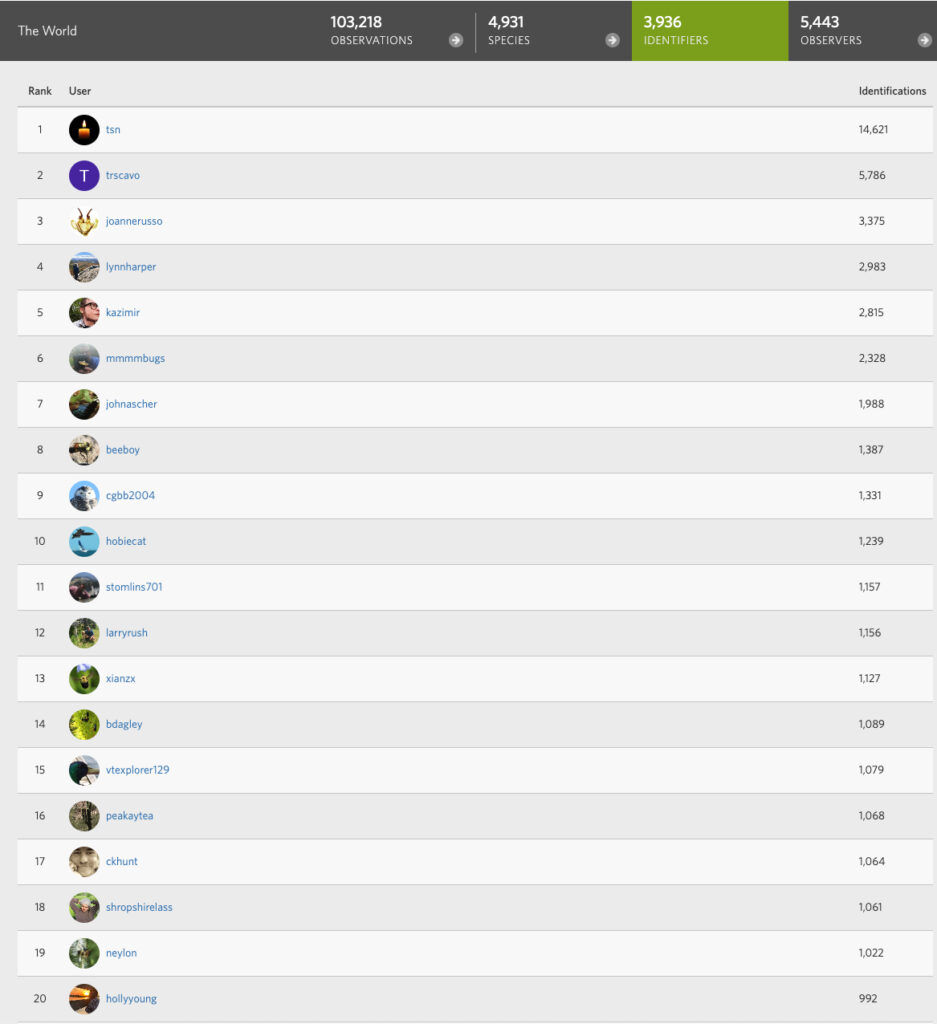

Identifications: It Takes a Village!

An observation submitted to iNaturalist becomes what is called ‘research-grade’ when it has a date, location, photos or sounds as evidence, and a 2/3 majority of agreement from the iNaturalist community identifiers. So far, for 2023 (identifications keep on coming!), there are now 103,218 research-grade observations representing 4,931 species. It takes a village for an observation to become research-grade. Other naturalists and scientists who can identify species help make these observations into research-grade data. We had 3,936 naturalists and experts help identify observations in 2023 alone.

These research-grade data are shared continually with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. This international open data infrastructure allows anyone, anywhere, to access data about all types of life on Earth, shared across national boundaries via the Internet.

Highlights of New species Discoveries in 2023

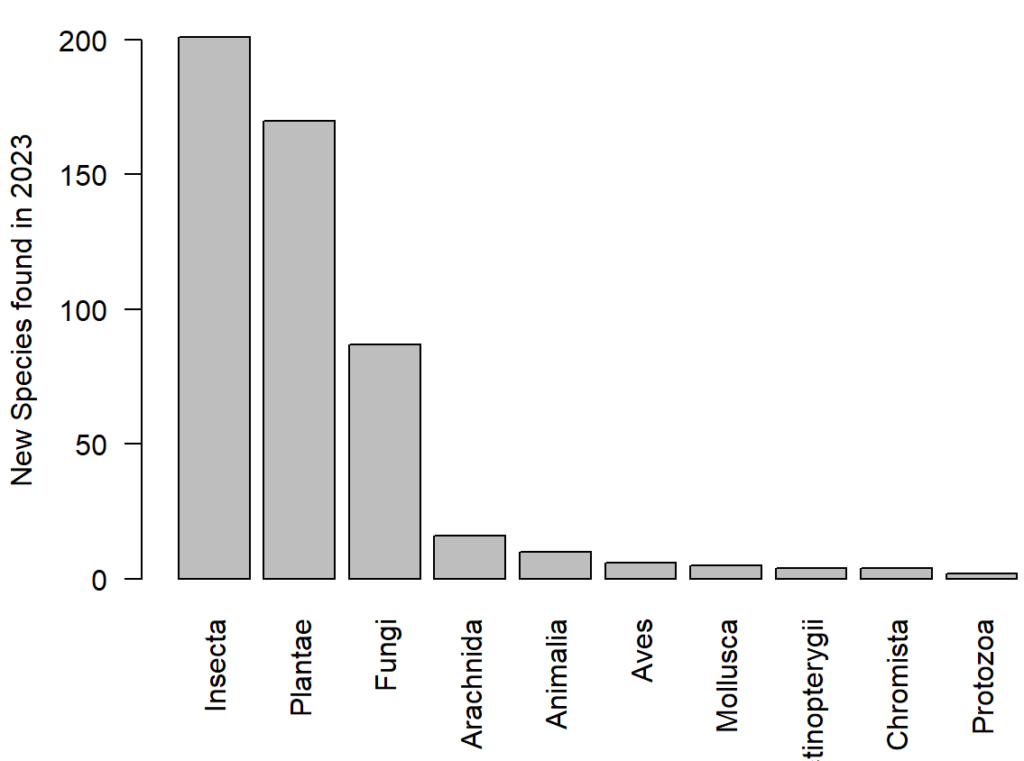

This year, iNaturalists added hundreds of new species to the database for Vermont; many of these are perhaps completely new discoveries for Vermont.

The number of new Vermont species added and verified in 2023 in iNaturalist. For some groups, especially plants, this might include some domestic or cultivated species that have not been filtered yet.

You can explore iNaturalist and find who and when the first record was reported for a species yourself. Just use the place tool for Vermont, search for a species, and mouse over the image. It will display the first observer. Click on it, and you will get a popup with the first and last sighting and more information to explore. But here are just a few highlights of species that caught our attention in 2023.

Bumblebee Photographed in Backyard is a New Species for Vermont

It took a photo, a drawing, a naturalist’s boundless curiosity, and bee experts from across the nation for Vermont to claim a new bumblebee species for the state.

It took a photo, a drawing, a naturalist’s boundless curiosity, and bee experts from across the nation for Vermont to claim a new bumblebee species for the state.

In 2008, artist and naturalist Susan Sawyer snapped a beautiful photo of a bumblebee in her yard. “I took this and many other photos of bees in my yard over the years,” said Susan. “In 2016, when I needed to draw a bumblebee, I used this one to work from.” She showed it to VCE staff at the time, and we knew it was a cuckoo bumblebee, but we weren’t sure which species. Then, we forgot about it. “The VCE team had ideas about what it was, but I don’t think they were 100% certain, with only this one photo; so, the drawing’s title was just Bombus sp., a Cuckoo Bumblebee,” she said.

This year, Spencer Hardy, VAL wild bee expert, joined Susan and staff from Four Winds Nature Institute to teach them about native bees. She remembered the bee in question and showed him the drawing. He knew immediately it was a cuckoo bumblebee and might be an interesting record. Spencer asked her to post the original photo to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist so he could easily share it with other experts and get their opinions, too.

Right away, Zach Portman, a bee taxonomist at the University of Minnesota, made the identification—Indiscriminate Cuckoo Bumblebee (Bombus insularis). Bumblebee expert Leif Richardson from the Xerces Society took a close look and agreed. World expert John Ascher, an Assistant Professor at the National University of Singapore and Research Associate at Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, concurred.

The Indiscriminate Bumblebee is native to western mountains and northern areas of North America. It belongs to the subgenus Psithyrus, the cuckoo bumblebees, which are social parasites of other bumblebees. The queens enter the nest of a host species, kill the resident queen, and then live and lay eggs in the nest. The host workers are forced by aggression and pheromones to rear the offspring.

This species has declined in some areas and disappeared from a few parts of its historical range. NatureServe ranks the Indiscriminate Bumblebee as globally vulnerable (G3), with Maine ranking it critically imperiled (S1) and New York calling it possibly extirpated (SH). Some of its host species have faced significant declines as well. Potential threats include habitat loss, pesticides, pathogens from domesticated bees, competition from introduced bees, and climate change.

Rare Butterfly Discovered after Two Decades of Searching

A rare and elusive butterfly was discovered for the first time in Vermont, flying this spring at one of the state’s protected natural areas. Bog Elfin, patterned in brown and rust and no bigger than a penny, had eluded detection in the state until one flew past a Vermont field biologist who had been searching for it for two decades. Read the whole entertaining story on the VAL blog.

A rare and elusive butterfly was discovered for the first time in Vermont, flying this spring at one of the state’s protected natural areas. Bog Elfin, patterned in brown and rust and no bigger than a penny, had eluded detection in the state until one flew past a Vermont field biologist who had been searching for it for two decades. Read the whole entertaining story on the VAL blog.

A New Native Miner Bee Discovered for Vermont

While exploring a swimming hole in Montpelier, Spencer Hardy, our bee biologist, stumbled upon a plant that he’s been trying to find flowering for several years, Sandbar Willow (Salix interior). Unlike other willow species in Vermont that bloom early in spring, Sandbar Willow blooms on newly grown shoots in late June and early July. This difference in phenology has important implications for the associated bees, as most of the willow specialists are done flying by late May.

While exploring a swimming hole in Montpelier, Spencer Hardy, our bee biologist, stumbled upon a plant that he’s been trying to find flowering for several years, Sandbar Willow (Salix interior). Unlike other willow species in Vermont that bloom early in spring, Sandbar Willow blooms on newly grown shoots in late June and early July. This difference in phenology has important implications for the associated bees, as most of the willow specialists are done flying by late May.

Returning a few weeks later in hopes of finding flowers, he was rewarded with his target – the second Vermont record of the Sandbar Willow Fairy Bee (Perdita maculigera). With the patch in full bloom, Spencer was surprised by the number and diversity of bees visiting, including many summer-active species previously not recorded feeding on flowering willows in Vermont.

After a few minutes, a bright red bee appeared and captured his attention. Knowing it was likely something unusual and a voucher specimen would be necessary to identify it to species, he carefully snapped a few photos before reaching for it with the net. A seemingly perfect swing somehow came up empty, and the bee disappeared. Ten minutes later, it briefly reappeared, but once again, it eluded his net and vanished. An hour later, the red bee reappeared and was quickly captured.

While the photos proved inconclusive, Spencer easily identified the mystery red bee under the microscope as Maria Miner Bee (Andrena mariae), a species previously unknown from Vermont. This species is widely distributed in North America but poorly known in the Northeast, with only a handful of recent records. Spencer followed up his late June discovery with a second record in early July in a patch of flowering Sandbar Willow in Alburgh.

New Neat Beetles Found

With over a million beetle species known worldwide, with perhaps another million left to be discovered, and over 30,000 species in North America alone, it is no surprise that iNaturalists are turning up new beetle species for Vermont each year. We found a few reports that caught our attention in 2023. In the spring, Nathaniel Sharp found the first record of Painted Hickory Borer (Megacyllene caryae) for Vermont in Bennington. Adults emerge in spring to lay eggs beneath bark scales on newly dead hickory (sometimes other hardwoods). The larvae feed for several weeks, then bore into the sapwood and later the heartwood. Pupation occurs in the fall at the end of a larval mine behind a wad of fibrous frass. Later in spring, Nathaniel struck again, finding a jewel beetled called Dicerca obscura in Monkton. More common in the southeast, where it feeds on various Persimmon species, it might feed on Staghorn Sumac here. In mid-summer, Bernie Paquette (who likely has many first state records on iNaturalist) found a tumbling flower beetle called Tomoxia inclusa in Jericho.

An Uncommon Moth on an Uncommon Shrub

The Speckled Casebearer Moth (Coleophora elaeagnisella) is found from Michigan and Ontario and northwestward, until now. In May, Kate Kruesi posted an image of cases on Canadian Buffalo-Berry (Shepherdia canadensis) in Ferrisburgh. The larvae feed on the leaves of Elaeagnus, Hippophae, and Shepherdia species and create a pistol-shaped case. Leafminer expert Charley Eiseman soon seconded the sighting. Check out his incredible Leafminers of North America e-book and consider supporting his amazing work with a subscription to it.

Explore the 2023 Photo-Observation of the Month Winners

Each month, iNaturalists’ fav’ any observation they like as a vote for the VAL iNaturalist photo-observation of the month. Check out the winners from 2022 (and other years, too!) and learn a little bit about the natural history of each organism.

New Report Uses Community Science Data to Establish Vermont Biodiversity Baseline

By 2100, Vermont is estimated to experience a net loss of 386 species (or 6%) under the current carbon emission scenario. This comes among several key findings outlined in a new report from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE). Their report marks the 10th Anniversary of the Vermont Atlas of Life, an ambitious project that harnesses the power of community science and professional biologists to discover, document, and map Vermont’s biodiversity.

By 2100, Vermont is estimated to experience a net loss of 386 species (or 6%) under the current carbon emission scenario. This comes among several key findings outlined in a new report from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE). Their report marks the 10th Anniversary of the Vermont Atlas of Life, an ambitious project that harnesses the power of community science and professional biologists to discover, document, and map Vermont’s biodiversity.

The report uses nearly 8 million observations from almost 12,000 species reported from across the state to help establish a biodiversity baseline for Vermont. As the researchers explain, this baseline is critical for understanding and measuring future biodiversity changes caused by landscape alteration, climate change, and other environmental perturbations.

“Using these vast amounts of species observations, we’re able to identify biodiversity hotspots and areas that harbor unique communities found nowhere else in Vermont. We’re also able to predict where they might be in 50 or even 100 years as the climate changes,” says Dr. Michael Hallworth, a data scientist at VCE and lead author of the report.

In addition to predicting future species loss, the report also found that current land conservation configurations may not be adequately protecting some of Vermont’s most at-risk species. By identifying areas that currently support unique communities—like the Lake Champlain Basin—Dr. Hallworth and his co-authors indicate areas that may be critical for maintaining biodiversity in the state.

The Vermont Atlas of Life (VAL) couples the power of volunteer community science with traditional biodiversity research and monitoring to quantify species diversity now and into the future. VAL joins others across the globe in curating species occurrence records at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), an international network funded by the world’s governments and aimed at providing anyone, anywhere, open access to biodiversity data. With these data, scientists and conservation professionals are discovering, monitoring, and solving biodiversity issues ranging from local to global significance, similar to the research team at VCE.

Although these species occurrence records are derived from many sources—from historical museum specimens to field observations—over 95% are submitted by community scientists through VAL-supported platforms like Vermont eBird, iNaturalist, and e-Butterfly.

“Vermonters have risen to the conservation challenge: our volunteer community scientists lead the nation with more field observations per capita than any other state,” says McFarland. “All of these data are curated at GBIF and searchable using the VAL Data Explorer on our website at val.vtecostudies.org/gbif-explorer. Without volunteer community scientists’ dedication to documenting Vermont’s nature, this report—and our work more broadly—wouldn’t be possible.”

These data provide the basis for many quantitative studies that can inform effective regional and global conservation decisions. In this report, the scientists draw upon this treasure trove of biodiversity data to better understand how many species there are and where they occur in the state. They also couple the occurrence records with climate and other environmental data to generate species distribution models, which allow inferences about what species may occur in areas of the state that are not well sampled. These models are essential for assessing conservation status and extinction risk, tracking population change, and guiding conservation efforts.

“The findings presented in this report allow us to see Vermont’s landscape in new ways. We’ve identified potential biodiversity hotspots and made predictions about future impacts of climate change on the state’s biodiversity,” concluded Hallworth. “Together, this information will help target land conservation efforts and much more.”

Help iNaturalist Vermont Surpass One Million Research-grade Observations!

We are now approaching 1 million research-grade observations. Let’s keep it going. You can help by sifting through all the observations of others and help to verify any that you can so we can keep growing our research-grade data. Add more observations of your own; no matter how common or rare the species is, every observation is essential. You can help annotate observations with life stages, phenology of flowering, associated species, and many more annotations that help make the data even richer for research and conservation. Let’s make it a million and learn about life in Vermont together! We hope you’ll join the project and help us make this biodiversity database grow. Make the Vermont Atlas of Life at iNaturalist your New Year’s resolution in 2024!